|

There's a point in every successful poem where the reader becomes emotionally entangled. We might call it the "heart-point" of a poem. It's that moment when emotional response begins. It can happen with a title, like "Tears, Idle Tears" or "Do not go gentle into that good night," or it can come at the end, as in Sylvia Plath's, "Strumpet Song." The feeling can be sadness, anger, joy, wonder, guilt, or any other flavor you choose. Whatever emotion you're going for, the heart-point in your poem matters. Let's take a look at a really simple two-line poem and see if we can find the heart-point. The poem is the teacher's favorite, "In a Station of the Metro,” by Ezra Pound, first published in 1913. In a Station of the Metro The apparition of these faces in the crowd: Petals on a wet, black bough. The heart-point isn't in the setting-making, technical-toned title. It isn't even in the word "apparition," although the word is pivotal to the poem's emotional impact. It's actually in the word "petals." And the emotion that starts there is hope. It's impossible for most of us to think of Spring or flowers without feeling at least a wisp of hope. The reader's hope, however frail, is engaged with this word. What comes next is a soft-landing, which Pound brazenly accomplishes by doubling down on traditionally banal adjectives. Remove the word "wet" and you have a crash landing. The word "black" is an intentional mortal shadow, but its threat is checked by the Holy Word "wet" which, in addition to its obvious sexual and religious connections, also has a lot to do with the chemical and biological foundations of life itself. So, in placing the heart point where he did, Pound captures the feeling of sudden realization that is the entire purpose of the poem. His satori-in-a-bottle finishes with lightning because you feel hope-fear-hope in such rapid succession. The heart-point of a poem is a vital element that many poets overlook, or underestimate. But the best poets not only know how to use it; they know how to use it as a foundation for brilliance. If you'd like some feedback for your poetry or a bit of help polishing your words, just click one of the buttons below. Or email @ [email protected] Archives May 2024

0 Comments

One of the sad realities of poetry is that virtually every poem misses more readers than it hits. Even famous poems, like "The Raven" or "Nothing Gold Can Stay," impress only a fraction of the readers who encounter them. When it comes to poems posted online, or poems published in journals, the odds of engaging the average reader are steep. Most readers don't finish poems, and even when they do read them all the way to the last line (without skipping), there's usually a point of disengagement before the last line falls. They may technically read all the way to the end, but their thoughts are on who did or didn't text back, or how the cat's doing, as they're reading. Way back in the candle-lit nineteenth century, Mr. Poe insisted that the longest any poem could be and still hold a reader's attention was 100 lines. That was a century before the Internet and social media. These days, many readers jump right from the title to the last line. This seems cruel to poets, and in some ways, it is a cruel reality, but it simply reflects the fact that, for most people, thirty-seconds of attention is a lot. Even from someone who's blood-related to you, or personally mentioned in your poem. A part of every reader is waiting for your poem to fail. It's a form of confirmation bias, which means the default assumption is: if you were any good, you'd already be famous. Since you're not, you must be bad. Then if anything is off in the poem, it confirms this initial idea. And by "anything" I mean grammar errors, typos, cliches, weak images, dull language, or glitchy rhythm and meter. The instant a reader (or editor) spots something "off" in your poem, they're going to scroll away, swipe away, or flip the page. They won't feel cheated, because poems are almost always free, but they'll stand confident in the idea that your work is average or below average and all they'll likely remember is the part that failed. AI can't (yet) help you with this issue. People don't read AI's poems, either. So what can you do? Two things. The first is to accept the reality of confirmation bias. The second is to eliminate all obvious errors in your poems. This means putting more time into each poem. It means setting new poems aside for a while and editing and polishing them after you've had a chance to get some distance. There's simply no other way. To be honest, this is very good news. There seems to be something in human nature that shrugs off the notion of "toss away" poetry, or disposable poems. I'm not saying that all poems should, be weighty or profound, but I think it's a very good thing that some part of us still expects something special each time we read a new poem. There's no shame in wanting artistry from an artist! So, the way to stop the scroll is to stop your own scroll and spend more time on each of your poems to be sure you don't provide convenient escape routes for readers. If you'd like some feedback for your poetry or a bit of help polishing your words, just click one of the buttons below. Or email @ [email protected] Categories All As I've mentioned many times, the best poems smack you in the nose with a bit of surprise. Some poems, like Allen Ginsberg's, "Howl," or Charles Bukowski's, "Girl on the Escalator," seem built almost completely out of surprise left hooks meant to knock you out of your normal senses. Other poems, like Plath's, "Daddy," or Sexton's, "You, Doctor Martin," turn the surprise volume up to eleven before they even really get going, just by striking an attitude of power from what society expects should be a victim's perspective. But poems don't have to be revolutionary or controversial to surprise. A single line, or even a single word, can suffice. For example, May Swenson's poem, "All That Time," burns straight into memory mostly due to her brilliant use of gender pronouns. By attributing "he" and "her" to two trees, and personifying their entangled growth, she captures a powerful poetic vision that is poignant and perpetually surprising. In fact, it's basically impossible to write a poem that doesn't do something new. Like snowflakes, poems are infinitely unique. Each poem is a one-of-a-kind "fingerprint" that speaks to a specific creative inspiration. Every time you write a poem, even when the poem fails, you make something fresh. It may be a Big Discovery that you proudly recognize, like uncovering a new theme or inventing a new stanza. It may be something you never even consciously notice, like using a perfectly placed slant-rhyme or dactyl. The point is: part of what draws poets back to writing again and again is the sense of discovery. And part of what draws readers back to your poems is the promise of surprise. The challenge is to integrate surprise into your poetry in way that draws attention, but also rings true. Diane Seuss's poem, "Glosa," is a perfect example of how to do this. Take a look at it by clicking the image above. The poem turns on the lines: ...Caligula, who cut off tongues and fucked his sister. This single punctuation-point of surprise, like a sudden uppercut, defines the entire poem and shatters its otherwise pensive veneer. The scholarly tedium of life and the wildest sense of perversion are combined in these lines to define the poem's theme, but also to wrangle something new with words. The lesson to take away here is to look at your poems like presents, both to yourself and to the reader. Wrap them carefully and make the impact of opening them an experience the reader will never forget. If you'd like some feedback for your poetry or a bit of help polishing your words, just click one of the buttons below. Or email @ [email protected] Categories All First impressions are very important when meeting new people. If you're introduced to someone and you have big pimple on your nose, or happen to be wearing your dingiest clothes, it's likely you'll feel a bit self-conscious. Rumor has it that your shoes are the first thing people notice about you when you meet them. So, today's blog is how to make sure you give your poems good shoes! And I'm not talking about titles or first lines, either, although those are crucial elements. What I'm talking about is the first word of a poem. That's where a poem starts to really walk and maybe even run or dance. But whatever it's going to do, the first word is the cue to action. Let's look at some examples, starting with Emily Dickinson's famous poem, "The Chariot." The word "Because" is a powerful starting point, almost of an equivalent scope to a larger phrase, like: "In the beginning." The first word promises something, and what it promises is: explanation. T.S. Eliot's "The Wasteland" starts off with the hopeful word "April" and then descends straight into Hell. Diane Seuss's poem "Self-Portrait with Sylvia Plath’s Braid," (linked above) starts with the word "Some" and proceeds to carve out a rebellious portrait of individuality. Robert Frost's, "The Road Not Taken" starts with the decision-word: "Two," and this initiates the reader into the poem's theme of choices. I could go on and on, but you get the idea: first words, like first impressions, set expectations and tone. They make moods. And if you get the first word wrong, it's likely the rest of the poem will follow suit. For example, there's a Ted Hughes poem called, "Buzz in the window" that starts with the word, "Buzz." Never mind the useless repetition, the word is so arresting and exciting that it should lead into something spectacular, but instead, the poem continues: "Fly down near the corner..." If you set expectations high with your first word, you have to start delivering fast. So keep that in mind. Hopefully these examples spark some ideas! Meanwhile, if you find these blog-posts useful, please consider buying me a spot of coffee through the link below! I could really use it! You can also donate here: PayPal [email protected] And if you'd like some expert help with editing or polishing your poems, or you just want a bit of feedback, hit the links below. Or email me at [email protected] I look forward to reading your work! Categories All I've collected a lot of rejection letters over the years. Most editors like to keep rejections short and to the point. Now and then, an editor will offer a bit of helpful advice. The best advice I ever received from a rejection letter came pretty early on in my writing career and it was just one sentence: "good writing offers the reader a clear window... " This advice works just as well for poetry or prose. The basic idea is that you avoid putting anything between you and the reader that makes it more difficult for them to "get" your message. This doesn't mean you can't write ambiguously, or even mysteriously, but it means you should always write with purpose and always be mindful of your readers. Here are some bad habits that make your "windows" dirty:

If you're writing prose, almost without exception, there are three things the reader must always know: who is on camera, what they are doing, and why they are doing it. Yes, you can blur the lines here for effect or to create suspense, but a little goes a very long way. With poetry the reader needs a good enough grasp on your images, rhythms, and theme to follow all the way through the poem. The good news in all of this is that simply being aware that writing acts as a "window" for reader should help. The even better news is, you can keep coming back to this blog for more tips! Categories All Images in the news and current events move us almost like planetary forces. When we see images like those that are coming out of Israel of rockets bombarding cities, hostages spirited away on motorcycles, fences bulldozes, houses razed, and families brutally slaughtered, we are rightly overwhelmed with emotion. As writers and creators we feel somehow it's our job to respond to earth-shaking events, no matter how morally inexplicable or horrendous they may be. We should feel this way. And it is our our job to respond as artists. But what I want you to consider today is how to respond to mind-shattering current events. And since the topic is so huge and important, I'm only going to make a single suggestion, but it's a pretty important one. Avoid the urge to be "epic." Sure, you can write a 500+ line poem or three-book series on the abduction of Noa Argamani by Hamas terrorists, but the odds greatly favor that your epic will fall flat. I've no doubt that the event will inspire someone to write a successful epic, but it probably isn't me or you. Instead, what we can do is use the image of her abduction, the feeling of it to inspire smaller, heart-first responses. I could cite any number of examples here, but I'm going to just use a single poem. The poem is by Yeats and it's called "Easter, 1916." This poem grapples with many personal and political themes, but it never loses its touch of personal intimacy. Without that touch anything you write about contemporary events will tend to gravitate toward editorializing, then degenerate to opinion, and finally collapse into some form of jingoism. What you bring to the table as an artist is the touch of intimacy the rest of the world seems to often lack. You're the heartbeat, the conscience, and the soul in a world that often seems heartless and soulless. So engage with current events, but do it with artistry. Meanwhile, if you find these blog-posts useful, please consider buying me a spot of coffee through the link below! I could really use it! You can also donate here: PayPal [email protected] And if you'd like some expert help with editing or polishing your poems or you just want a bit of feedback, hit the links below. I look forward to reading your work! Categories All Here's a really simple branding tip that can be used by any writer or poet and, if you do it right, it can be oh-so-powerful. Ready?

Here it is. Add a touch of mystery to your brand. Whether it's a secret ingredient, a guarded maker's method, or an exotic family history, people are naturally drawn to mysteries. Sometimes not knowing who the author is can be the best method of all, as in the case of the unjustly famous "Simon" Necronomicon. But that won't really work for us. And despite appearances, I'm not suggesting that you really need to do anything dramatic. A simple touch will do. For example, in your author bio you could write something like Banna Bestpoet once lived in a haunted apartment building and her experiences there are reflected in what she writes. Or, Ned Novelmaster was once bitten by a colorful and (currently) unidentified species of snake while hiking in Indiana. You could also dig around into your past or your family lineage to see if you can find something interesting to base your mysterious touch on. Another route is to posit an iconic goal like: Sarah Screenwriter has spent years studying the principles of perpetual motion and hopes to someday build a perpetual motion machine. The most potent mysteries have to do with (of course) sexuality, cultural heritage, money, religion, death, and crime. I'll leave it at that. Is it OK to lie? Well, yeah, but if you do, don't say a lot of lies, just slip one in. I learned that when a talkative and deceitful Sherpa rescued me from freezing to death during a failed climb on Everest. Meanwhile, if you find these branding posts useful, please consider supporting the site. Your contribution is invaluable in allowing me to offer the content. PayPal [email protected] You can get Five Big Branding Tips thru the link below. Pick up my Seven Secrets of Poetry Manual also linked below. And if you'd like some expert help with editing or polishing your poems or you just want a bit of feedback, hit the links below. I look forward to reading your work! The most important thing in business is branding. The same goes for celebrities. But what many writers don't realize is: it's also true for poems, stories, and novels. It's obvious if I mention someone like Stephen King or J.K. Rowling, but it's just as true for Lord Byron and Jericho Brown.

When it comes to iconic writers in any genre, you get a picture and a feeling just from the sound of their name. You can also spot a piece of their work in an instant. This is what it takes to really get over the top as any kind of artist. You need to create an immediate association between your name, image, and a particular niche, archetype, or signature style. For most artists this means some degree of self-restraint and submission to audience capture. Mick Jagger at 80 years old just released a new Rolling Stones song and guess what, it sounds like the Rolling Stones sounded in the 1970's because that's what people expect and desire. The Stones and Jagger could play anything at this point, and have done so. Go listen to Super Heavy. But no-one liked Super Heavy, not as much as they liked the Stones, anyway. So how do you do this? And if you're already doing it, how do you do it better? The good new is, there are answers to those questions. The bad news is, they're not a simple answers. If it was easy, we'd have even more celebrities running around than we already do! I'm going to give you the answers over the course of the next few blog posts. So stay tuned. The place to start even if you've already published or posted and have fans and followers is: always do good work. Think of your work as food you're offering to people. If it's burned or bland, why give it to them. They're not starving. The only reason to offer your work is if you feel it's delicious, or deliciously bitter! So, the first step in any brand is: consistent quality. Don't hurry to get your work out; focus on making it taste good. And serving it in the right place at the right time with the right atmosphere. I'll dig in deeper on how to find out what your brand is and how to push it to the front of your creative efforts in my next post! Meanwhile, if you find these blog posts useful, please consider supporting the site. Your contribution is invaluable in allowing me to offer the content. PayPal [email protected] Pick up my 7 Secrets of Poetry guide to help write and polish your poems on your own, for a mere $5.00 right now through the following special link: https://www.buymeacoffee.com/writerdanq/extras And if you'd like some expert help with editing or polishing your poems or you just want a bit of feedback, hit the links below. Most of us write with at least one poet always on our minds. Some of us have numerous poetic "ghosts" flitting around us as we hammer away at our work. Whether it's Shakespeare, Tupac, Diane (or Dr.) Seuss, some of the voices in our heads aren't our own. Not wholly anyway.

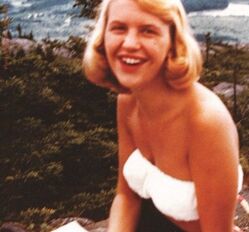

It's a kind of cognitive alchemy where we read our favorite poets, the words take up a living space in our imaginations and they become part of us, where, in doing so, they change into something new altogether. This process of mingling minds is what poetry's all about, really. It's a soul to soul contact sport. And here's the really interesting thing about it: it doesn't matter who you are, or where your work is presented, if you do a good enough job as an artist, your words will pitch a tent in someone's mind, potentially a lot of someones. So think carefully about what you're offering. If your poems rub people rawly, this can be a very good thing for sparking thought. But if your poems leave people with a sick or miserable feeling, they'll avoid them in the future, unless they are one of the rare types who wants to feel miserable. I'm not saying you have to write happy things all the time; I'm saying: be aware that poems are like songs. They infect people. They're sticky. A great poem sticks even more than a great song. Even a single line such as : "Rage against the dying of the light" or "To be or not to be" can ring for centuries. The voices of poets in your head aren't trying to tell you how to write. They're trying to tell you why we write. If you remember that, you'll make better poems. If you find this poetry tip useful, consider picking up my Seven Secrets of Poetry guide. It's packed with tips and tricks. You can get it through the link below! Also, if you'd like to support the blog, I'd really appreciate your much-needed donation through PayPal [email protected] And if you'd like some expert help with editing or polishing your poems or you just want a bit of feedback, hit the links below. "Wintering" is Sylvia Plath's triumphant declaration of victory and joy. Victory at having found the world of honesty and truth that she sought her entire life, first as a scientist following in her father's footsteps, then as a poet, searching beyond the gates of self-identity and death for the reality she intuited might exist beneath the world's often superficial surface. Joy is what she found under that surface. The poem is part of her "Bee Sequence" and I suggest you read the whole set of poems sometime. For now, we'll concentrate on just "Wintering," (click picture above) which is the final poem of the sequence. The poem starts with the line: This is the easy time, there is nothing doing. What? I thought this was a Plath poem? How could the writer of "Daddy" and "Lady Lazarus" start a poem this way? Didn't she kill herself? What's going on here? The truth is, Plath found immense joy, creative peace, and unstoppable inspiration in her experiences with the loss of personal identity. It is similar, but not exactly the same as, what reportedly happens to some people who take psychedelic drugs. Plath didn't use psychedelics, but the breakdown of her "ego" and her ties to the world of "mendacity" even for a short period, through her encounters with poetry and nature, revealed an illumination that not only made her poetic name, but changed the entire world, and is still growing. In "Wintering" she enters the cellar of an unnamed aristocrat in a spare house she has rented. This is a symbol of the abyss, the "blackness and silence" of the Yew tree, the All Being of nature. Only now Plath has no fear of the void, she has made a home for herself there. But it is not based on materialistic things or titles such as "Sir So-and So's gin." Instead it is based on an abiding -- perhaps eternal -- connection with the rhythms of nature. She has become Queen of the Bees, just as her father, Otto, was known as King of the Bees, but as Queen she doesn't want to control nature, she simply wants to perpetuate it. She has learned from her encounters with nature to see life, not death, as the impetus of being. She has regained a personal identity, but it is a greater, much wiser and more enduring self-identity than she had as "Ted Hughes's wife." This is how we should remember Plath, because this is the poet she truly was... Her tragic suicide was the result of her inability to stay in this moment of illumination, but she touched it and she left a record to inspire countless generations to come. So in a sense, she did stay rooted in it. This concludes my first blog-post series on Sylvia Plath, but it won't be my last! If you enjoyed the posts, please consider making a small donation to my PayPal, or use the Buy Me A Coffee button to make a donation through my MusicGuru page. I could really use the support right now!! https://www.buymeacoffee.com/writerdanQ Donate via: PayPal: [email protected] CashApp: $writerdan Categories All |