|

I've collected a lot of rejection letters over the years. Most editors like to keep rejections short and to the point. Now and then, an editor will offer a bit of helpful advice. The best advice I ever received from a rejection letter came pretty early on in my writing career and it was just one sentence: "good writing offers the reader a clear window... " This advice works just as well for poetry or prose. The basic idea is that you avoid putting anything between you and the reader that makes it more difficult for them to "get" your message. This doesn't mean you can't write ambiguously, or even mysteriously, but it means you should always write with purpose and always be mindful of your readers. Here are some bad habits that make your "windows" dirty:

If you're writing prose, almost without exception, there are three things the reader must always know: who is on camera, what they are doing, and why they are doing it. Yes, you can blur the lines here for effect or to create suspense, but a little goes a very long way. With poetry the reader needs a good enough grasp on your images, rhythms, and theme to follow all the way through the poem. The good news in all of this is that simply being aware that writing acts as a "window" for reader should help. The even better news is, you can keep coming back to this blog for more tips! Categories All

0 Comments

When the speaker of the poem in Plath's, "Medallion," picks up the dead snake and looks it in the eye, everything changes. Plath's view of death changes, her view of nature changes, and -- most importantly -- her poetry changes. It would never again be the same. I know this seems like a very strong statement, but I can back it up. First of all, Plath's gesture in taking the dead snake in hand is more than a Freudian castration fantasy and it's more than a throwback to the Biblical rebellion of "Sonnet to Satan." What she's doing in this poem is more, even, than striking a blow for Mother Earth and ecology. Although she's definitely doing that. To fully understand what's going on in the poem, we need to tap deeply into a single word: the title. The first thing to note is that it's a single word. It suggests unity and wholeness. Like the roundness of a medal. I wonder if you are aware that the word "medallion" applies to more than a medal, or a carving in a wall. It actually can also mean a small serving of meat. And this is the aspect of the word that's really important here. Plath's husband, Ted Hughes, was very well known as a "muscular" poet, centered on nature, who often assumed the perspective of predators, like jaguars, gar, or foxes. He was an alpha male of a guy. So let's tie that to another quick biographical insight into this poem. It was written at a writer's retreat called Yaddo that was only for the cream of the crop -- and Plath was there as a guest of her husband, who was actually in residence there as a poet. She was a tag-along. A small serving of meat. Now deeply consider this as you read the poem again (click Plath's picture above). The setting is Yaddo. Plath is alone. She finds a dead snake by the gate and picks it up, bonds with it, and in doing so not only gains a "medal" of individuation and poetic purpose, but also learns something about the nature of predation and the heart of nature itself that her nature-poet husband seems to have missed.... These lines are a description of the beginning of what she learned: Over my hand I hung him. His little vermilion eye Ignited with a glassed flame As I turned him in the light; It is at this precise moment that her unique voice and purpose as a poet is truly initiated. But to gain it she has to see through death. Her poetic voice is dependent on seeing through death. It is also at this point when the premonition of her marriage break-up (as shown in "A Winter Ship") starts to prove itself true. But more on all this next Monday*, as I finish up my analysis of this incredible poem. Yes! The poems is worth three blog posts! It's probably worth an entire book! Poem tally as of today: 7-30-23: Poems Written: 325 Poetry Submissions: 51 Rejections: 24 (14 tiered) Acceptances: 0 Poem written today: "Skull Money" Want a little help polishing or editing your poems? Contact me: [email protected] OR use the links below. * If you're feeling really ambitious, please look up the Melissae, find all the stuff about bees and seeing past the veil of death through poetry, and consider how this all relates to SP, synchronistically. Categories All Plath's poem "Medallion" marks a powerful turning point in her poetry. Prior to this poem, Plath's encounters with nature describe a seeking, almost childlike vision. In poems like "Black Rook in Rainy Weather" or "Full Fathom Five" we encounter descriptions of nature that are partly naturalistic and partly mythological. This fusion of rational and mystical response is what Plath does best, but before she wrote "Medallion," there was an invisible, but quite firm, barrier between her and the natural world. Plath's father was a biologist who specialized in studying bees. He was affectionately known by his students as "King of the Bees." For Plath, initiation into nature was primarily a scientific affair, but it also carried a mystical, spiritual aspect as her father guided her to see nature with reverence and curiosity. Plath's husband, Ted Hughes, was a "muscular" poet well-known for his poems on nature and animals. What makes "Medallion" so special is that the poem marks the exact moment in Plath's development where she drops her "inherited" patriarchal vision of nature and initiates herself into a personal, more feminine and much more mystical vision of the natural world. This is the poem where she moves away from her father and her husband's view of nature as a setting for competition, dominance, and predation -- and begins to feel herself as an artist connected to the rhythms and mysteries of nature. The first lines make it clear that this is a mystical initiation, a spiritual, magickal encounter: By the gate with star and moon Worked into the peeled orange wood The bronze snake lay in the sun Believe it or not, to an old alchemist such like me, the whole of mystical transformation is laid out in this single stanza. The table is set, the stars are aligned, and we are already at bronze stage. One key element here is that, quite rightly, the bronze state of alchemical process is connected, deeply connected, with death. The message here is not: death is the power that transforms, but rather, death is merely a stage of transformation and not just literal death, but also symbolic death. So here we have a dead snake, exploding with Freudian overtones, in a setting of witchy nature, with a lone speaker, a poet, left to contemplate a world where men have seemingly vanished but left behind an enduring statement. As the lone woman of the woods, an "Eve" so to speak, what does the speaker of the poem do? She picks up the snake. And that's when things start to get really interesting. Click the pic above to read the poem and then come back next Monday to read the rest of my analysis!!! Poem tally as of today: 7-24-23: Poems Written: 318 Poetry Submissions: 51 Rejections: 24 (14 tiered) Acceptances: 0 Poem written today: "Sea Bacon" Categories All AI is writing poems. Lots of poems. So many poems that the already overflowing sea of poetry on the Internet and elsewhere is the literary equivalent of Biblical deluge. Anyone can now write a poem literally just by tapping their finger. Sure, the poems (for now) aren't very good. And, sure, they are brazen pastiches of copyright trampled "samples" based on wiki-prosody and plebian twangs. But AI is only going to get better. I have a lot of thoughts about this, but right now, I want to know what you think. Do you fear AI? Do you use AI for writing? Do you scoff at the idea? For now, I'll just say this... I watched this happen with chess. One day people were laughing at computers, next thing you know, the ten best players in the world combined, led by Magnus Carlsen, would be lucky to even survive a middle game against super-crushers like Leela and Stockfish. Carlsen is the highest rated player in history at 2800, while Stockfish is rated at 3600. A human being will never beat the best AI at chess. Never. But imagining that it could happen would make a great story! Or even a poem. And, so far, no AI could have thought of that. If you click the John Henry portrait up top, you'll see how I've been leaning on AI creatively. No "tally" because I'm taking a quick break from poetry to work on music. Please take a moment to check out my new song "Wyld Heart" over at YouTube. Or click over to my Soundcloud page! Categories All My recent post on "Bitter Enders" received a nice response. Thanks to everyone who read the post and replied to me about it. Your comments and ideas are deeply appreciated! It's a privilege and a pleasure to share thoughts with each and every one of you!

Never be shy about reaching out to me to talk poetry! Just my email or contact me through Facebook. One of the most powerful insights on the topic of emotional well-being came from poet Cindy Creel, who wasn't actually responding to my blog post, but to a poem I posted. She wrote: "describing the way something made you feel is a place of strength." Words to live by! This is another way of saying: poems heal. Reading a poem, writing a poem, dreaming a poem. In each and every case, poems provide inspiration and -- often -- hope. People have written poems in concentration camps, mental wards, country jails, deserts, and on rafts lost as sea. It's natural to go through bouts of bitterness, alienation, doubt, and envy in your life as poet, but don't let these emotions define you or your experience with art. Poems, offered by anyone, at any time, are acts of love. Or should be. Even when poets write with deep anger and bitterness like Rimbaud or Plath's -- poetry, at its most destructive -- remains an act of creation. Poets grow things like ideas, moods, spirits, themes and, sometimes, myths. Cindy also notes the deep relationship between physical well-being and emotional well-being, starting right from the earth up. You need to literally get your hands dirty. Soil contains minerals that are essential to your mental and physical well-being. I overlooked these priceless insights in my original post. So let's state it clearly now: You need to eat right, you need to get outside, and you need to put your hands in the dirt. So hike, bike, garden, jog, or just sit on a blanket under the stars. Take a sip of puddle water off your fingertips, touch a spiderweb, eat a blade of grass. Rub some dirt on your face. Suck a pebble. Inhale the reviving scent of the earth. Keep yourself, healthy, sane, and inspired so you can joyfully share your creative works with all of us for many years to come! Tally Poems Written: 313 Submissions: 51 Rejections: 21 (13 tiered) Acceptances: 0 Poem written today: "n/a" Mixing song "Global Rain" If you need a hand revising and polishing: 1) Have me do it for you! Click the "Poem Polisher" button below. I've helped lots of poets. 2) Use my 7 Secrets of Poetry pdf as a guide for revision. I've met an awful lot of poets. Most of them make my heart soar and do something to bolster my faith in humanity. Some even take my pain away, or explain it to me so beautifully I don't want it gone. But a few leave me feeling truly sad and frustrated. Who are these few poets? I call them the "bitter enders." Poets who, for some reason or another, seem to feel as though they've been jilted by the muse, or by fate, and they're out to let people know about the injustice. The first sign that you're dealing with a bitter-ender is when someone says something like: "You know, there's a lot of poets out there and they all suck. What they're doing isn't real poetry!" If you look at that statement closely, you'll see the poet has taken on two extremely heavy burdens: the first is, they are apparently the world's best poet, no easy job; second, they are an accomplished critic, a similarly Herculean task. Outside of Poe, I would have thought the odds were against such a pairing. Bitterness is always lurking in wait and once it gets hold of a poet, it turns them into something snarly and pathetic. So if it starts to hit you, fight back fast! Here are some things I think you can do to shake off bitterness when it bites: 1) Go out in nature and be quiet for ten minutes. Do this every day if needed. 2) Try writing about an entirely new subject. If you've never written a poem about pogo-sticks write one now. 3) Watch a stupid movie that makes you laugh. 4) Set more realistic goals. Yeah, you may not win that Nobel Prize for Poetry, but can't you still be happy? 5) Consider taking a break from creative work. If necessary, a long break. That last one may seem harsh, but seriously if it's not fun anymore, if you're really angry and frustrated and resentful of other people's creative doings, it might be better to just put down your brush. If you're not over-brimming with passion when you work and see other poets' work, you may not realize it, but this is a sign that you've probably just stayed too long at the party. Or showed up at the wrong house. What won't work is stalking people down one by one to tell them how great you are (or were) and how lousy everyone else is -- trust me, no-one's listening. Speaking of listening, why not check out my new song "Coming Home" at YouTube? Tell me what you think of it. Just click the button below!!! Tally Poems Written: 312 Submissions: 51 Rejections: 21 (13 tiered) Acceptances: 0 Poem written today: "Meandering Poem of Magick" Categories All Each time you write, submit, or publish a poem, you risk rejection. Believe it or not, rejection from editors is not the worst kind of rejection. It's rejection from readers (and critics) that stings the most. When an editor rejects your poetry, you can at least comfort yourself by submitting the same poems elsewhere.

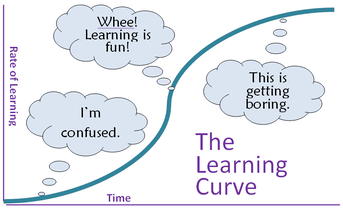

If a poem is published or posted and people slam or ignore it, getting a mulligan can be problematic. Not impossible, just challenging... Another thing is: you're going to get rejected no matter who you are. You could be Shakespeare and you'd still get your fair share of rejections. So what do you do? Well, I've had hundreds if not thousands of rejections and I can offer the following insights: 1) Expect to get them. Just like you accept getting sand in your stuff when you go to the beach. 2) Never answer them. Not privately by messaging the editor, or publicly, by whining to your social media circle. You can post an update as in "I was rejected today..." But resist the urge to defend yourself or criticize. 3) Take a close look at your bio and cover letter. Can you make improvements? If you have a dull bio (I do!) or a rambling (or sloppy) cover letter, it will likely influence editors' decisions. 4) If a poem has been rejected by more than 5 venues, see if it may need improving. Sometimes it's just a single line or even a single word that's putting people off. 5) Move on. Resubmit. 6) Only submit your best, most fully polished work. When an editor asks to see more work from you, they really mean it. If they don't make that specific request, you shouldn't read much else into the rejection. It's important to guard against the hurt of rejection because you can really get sidetracked by the glums. I'll talk about how to deal with online rejection, social media hate, and critics in a future post. Tally Poems Written: 311 Submissions: 51 Rejections: 21 (13 tiered) Acceptances: 0 Poem written today: "N/A" Still mixing song, "Coming Home." If you need a hand revising and polishing: 1) Have me do it for you! Click the "Poem Polisher" button below. I've helped lots of poets. 2) Use my 7 Secrets of Poetry pdf as a guide for revision. Being a poet means engaging in a process of lifelong learning. No matter what you do, or how hard you work and study, you'll never master the art of poetry. But writing poems can help you master yourself. Believe it or not, this has something to do with the topic of rejection. When people ignore your work, reject your work, or criticize it, you're on the road to learning. Usually that road is very painful and involves a lot of frustration, soul-searching, maybe even swearing of vengeance. The point is, you'll be a different person for the experience no matter what. Whether you're a better person is up to you. The important thing to remember is that being a poet means embracing growth and change, both in your writing and in your life. Writing poems can help you connect with others and that's a wonderful feeling. But never forget the power that writing poems has to help you connect with you. Both who you are now, and who you might become. Tally Poems Written: 311 Submissions: 51 Rejections: 21 (13 tiered) Acceptances: 0 Poem written today: "n/a" Mixing music track "Coming Home." If you need a hand revising and polishing: 1) Have me do it for you! Click the "Poem Polisher" button below. I've helped lots of poets. 2) Use my 7 Secrets of Poetry pdf as a guide for revision. Categories All Tell me if you agree with any or all of the following:

In my personal life, I like it best when I'm not being told what to do. Freedom and self-determination appeal to me a lot. But with creative works, I often feel drawn to traditional rules and modes. Not exactly old fashioned, but I'd say I'm more reluctant than some poets to get into wild experimentation with form or language. How about you? I, of course, have copious thoughts on each of those points above, but I'm more interested in your thoughts. Do you think rules are made to be broken? Or do poets need them? So let me know at [email protected] OR [email protected] OR just leave a message through the form below. Tally Poems Written: 311 Submissions: 51 Rejections: 21 (13 tiered) Acceptances: 0 Poem written today: "Elm" If you need a hand revising and polishing: 1) Have me do it for you! Click the "Poem Polisher" button below. I've helped lots of poets. 2) Use my 7 Secrets of Poetry pdf as a guide for revision. If you order a polish in May you get the 7 Secrets book free!!! Categories All I talk a lot about emotion in these blog-posts and the reason is because all good art, particularly poetry, is made of emotion. If you aren't willing to express emotion intensely, there's really not much point in trying to be a poet. The same is true if you just want to express one emotion over and over. If your poems are always happy or always sad, people will get bored with your work fast. The best thing you can do is to use a lot of different emotions, even in a single poem. I could cite hundreds of examples here, but let's just focus on two really famous poems. The first is "The Raven" by Edgar Allen Poe and the second is "Lady Lazarus" by Sylvia Plath. Sure, "The Raven" is famous for being synonymous for mourning, and rightly so, but if you look at the poem carefully you'll see it actually runs a gamut of emotions from boredom, to hope, to anger, and terror. Unrelenting grief is only one emotion, and it's profound, centuries strong sadness would not ring as fully as it does without a compliment of contrasting colors. Plath's poem is even more dynamic. It starts with submissive emotions of fear and self-loathing and rises to emotions that are best described as "godly." Along the way, Plath uses sarcasm, honesty, pity, anger, joy, and nostalgia to fuel her transformation from victim to avenging Goddess. That's what you want to do with emotion in a poem. You want to use it as both color and tempo simultaneously and you want to color with more than one crayon and keep time on more than a single drum. Tally Poems Written: 308 Submissions: 51 Rejections: 20 (13 tiered) Acceptances: 0 Poem written today: "Sisters" Categories All |