|

Should you ever just give up on a poem? Some poems come out almost fully formed, just perfect straight out of the fire, like a gift from from the gods. Others have to be wrangled, sawed, sanded, polished and, in some cases, given a full body-transplant. What makes it worse is, a poem can be this close to brilliance and then it takes months and sometimes years to actually get it right. So you have a decision to make as a poet. Luckily, you get the chance to make the decision over and over. Basically, what you have to decide with each poem is: how much can revision help? Usually the answer is: a lot. Even if you only make small changes or a small change to a given poem, the results can be dramatic. There are times, though, when you just have to let go. Some poems just fail. Unfortunately, there's no rule when it comes to making this judgment call. And it's liable to be different, in any case, for each poem. Given, these vagaries, here's a few points that I've found helpful over the years:

I also have a thought on not revising or refusing to revise your poems: that's why your poems aren't working for anyone else but you. So do your poems a favor and shine them as best you can. If you hate revising and polishing, consider two options (best used together!): 1) Have me do it for you! Click the "Poem Polisher" button below. I've helped lots of poets. 2) Use my 7 Secrets of Poetry pdf as a guide for revision. Tally Poems Written: 307 Submissions: 51 Rejections: 20 (13 tiered) Acceptances: 0 Poem written today: "Street Steel" Categories All

0 Comments

My name is Daniel E. Blackston, and I have the following bad poetic habits:

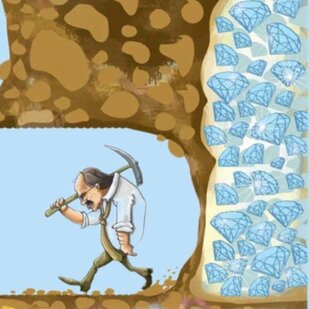

1) I use words nobody understands. (Rhetoric) 2) My poems are too dense. (Accessibility) 3) I sometimes lose track of my theme. (Obscurity) 4) My closing lines could really be better. (Finishing) Don't get me wrong, it was hard to say those things publicly. And hard to say them even to myself. But this is the reality I face as a working poet and some version of it is your reality, too. If you think you don't have weaknesses, you're mistaken. There are no perfect poets. Some are very close, sure. But no-one gets it right all the time. Poets tend to carry their mistakes along with them and are reluctant to change. Look at Dickinson's galloping meter, Crane's obscurity, Plath's melodrama, Eliot's banality, or Poe's sing-song rhythms and rhyme. Sometimes the mistakes work for you, and that's probably why we cling to them, but -- for the most part -- our bad habits restrict our growth. At the very least, our bad habits show us where we can immediately try to improve. For me it's: have a point, say it clearly, and finish strong. How about you? Can you name your bad habits? Tally Poems Written: 306 Submissions: 51 Rejections: 20 (13 tiered) Acceptances: 0 Poem written today: "Tall Flowers" I actually think competition is good for poets. From ancient days of yore when Greeks competed for laurel crowns right on through to today's poets trying for the most "likes" on social media, competition can be like electricity -- a source of fuel and excitement to keep you moving. Competitors are mentors. On the other hand, if you take it too far, you can crash and burn. So how can you tell when competition is healthy? Here's a few good signs: 1) You're inspired to write a lot. Not just about poetry, but actual poems. 2) You get excited when you see a new poem by your competitor (s). 3) You accept that you probably can't better what the competitor does best. 4) You integrate as much as you can from the competition even if it means doing away with some of your most treasured habits and riffs. 5) You feel or see a path forward for your own work and feel that you have energy for the journey. Now here are signs competition is getting to you: 1) You naysay your competitor's work. 2) You feel you've been treated "unfairly" by life, or readers, or publishers. 3) You refuse to edit, change, or revise your work. 4) You dig up old works that you feel never got their just due and wave them around even if no-one seems interested in them. 5) You have problems sleeping or concentrating on your work because you're busy trying to cut your competition down to size in your imagination, or dream up compensatory strengths for yourself. In any case, the point where you no longer feel the least bit competitive is when you'll probably start to lose interest in creating new things. Or you may just start repeating yourself. Competition keeps us fresh and "young" and, well, no matter how good you get -- you can always find someone to envy! Click the pic above to read about a very famous poetry competition! Categories All Rote memorization has always been associated with poetry. Poets who can recite from memory get applause. It's equally impressive if you can quote Lord Byron or Mya Angelou from memory. It's only slightly less impressive if you can quote one of your own poems without a book or phone. That's why I want you to commit to memorizing one of your poems, with the intention of carrying it around in your head, ready to drop at any given opportunity. It should be a short, powerful, unforgettable poem. But if you can't manage that, it should at least be short. Don't overwhelm people. And don't add to much dramatic flourish to your reading. Let the words do the talking, or you'll seem too rehearsed. Once, in a car full of his female friends, a poetic rival challenged me to recite one of my poems. Luckily, I was up to the challenge and -- when I finished the poem -- everyone clapped. If I showed you the poem right now, I promise you wouldn't clap! It's not a great poem. What got people clapping was the fact that I could recite without flaw, from memory. It's like watching someone play a song right in front of you, or rap in front of you. They may or may not be a pro, but there's a natural excitement in just being around any decent live performance. So, do me a favor. Memorize one of your best, short poems. Then, if you want to, memorize another one later just so you don't look like a one-hit wonder. Tally Poems Written: 305 Submissions: 50 Rejections: 19 (12 tiered) Acceptances: 0 Poem written today: "N/A" * Three music demos recorded* Categories All Practicing any art at any level for any reason is a Good Thing. You don't need to make money, you don't need to move mountains, you don't need to dominate Tik Tok, Instagram, or Twitter. You don't need your face on a billboard or your hands printed in cement to get 100% of everything that art and creativity have to give. Fame and money are not art. They have nothing to do with art. Our culture confuses this beyond the ken of the average person to tell the difference, but that doesn't matter. The reality is: you can be rich and famous without talent and creativity and you can be a creative genius who doesn't have a follower or a dime. So what do you get our of being an artist that's not based in money or fame? It's a long list. There are items on it that, if you're not an artist, you probably haven't thought about since you were a child and wouldn't have known you lost until you found them again. When you see a work of art, part of the shine that comes off of it is that childlike imaginative power that's a direct connect to life. That freshness of discovery, self-expression and wonder. Artists live there. Your art will keep you healthy, happy, busy, and engaged with life until you no longer need it, or until your brush falls out of your dying hand. In any case, your life will be better, more exciting, and you'll bring joy to others by making art. So my advice is: do it. Tally Poems Written: 304 Submissions: 50 Rejections: 17 (10 tiered) Acceptances: 0 Poem written today: "Animal Dreams" Categories All I've been writing a lot of poetry lately and I've noticed that there's a big difference between inspiration and theme. By this I mean: you can get inspired by something, say the sight of the sun on a lake, but when you write the poem about the sun on the lake, the theme that comes out will almost certainly be something different than what you expected or felt when you got hit with inspiration. It's not always that way, but it's often that way. What's more, it seems as though the best poems are those that start from a point of inspiration but travel somewhere new, somewhere previously unknown. This may, in fact, be one of the reasons that what we call "inspiration" feels so thrilling, because we instinctively know we're about to travel somewhere new. For me it's much more vital to follow inspiration than theme. If I start out thinking "I'll write a poem about how bad war is..." The results are usually blah. If I start off thinking, "Wow, the way that tree-shadow looks on the street is cool..." I often get good poems. I'm sure some poets are theme-first and there's nothing wrong with that. For these poets, theme is inspiration. But I maintain it's not always necessary to know your theme, and, even if you think you do, it's very likely others will see something different. So don't get too attached to your themes. The opposite goes for your inspiration. Stay as attached as you can!!! Tally Poems Written: 302 Submissions: 50 Rejections: 17 (10 tiered) Acceptances: 0 Poem written today: "Off-Task" Categories All Clearly, poetry is a dangerous business. Brilliant poets like Hart Crane, Sylvia Plath, and Dylan Thomas lost their lives prematurely to substance abuse, mental illness, and poetic ambition. Others, like Robert Lowell or Ted Hughes descended into a kind of tedium of accomplishment and self-satisfaction that, to any working poet, appears worse than actual death. Most of us don't risk our lives for poetry, or our sanity, we just write poems and suffer a lot about how many people read and like them. But is this kind of worrying unavoidable? There's actually a kind of golden path that even the most sensitive creator can follow to artistic fulfillment and a happy life. The key is knowing and remembering that it's all about creativity and growth, not about popularity and "likes." I'm not saying there's anything wrong with being popular. I'm saying, don't worry about it one way or another. The more you worry, the less you'll create. Fortunately, there's a single all-purpose cure for burnout: just keep creating. Push yourself hard everyday and stay excited and inspired. If you dig deep enough, "likes" and followers will take care of themselves. Tally Poems Written: 299 Submissions: 50 Rejections: 17 (10 tiered) Acceptances: 0 Poem written today: "Sky with Machines" Categories All Have you given up things for poetry? Do you feel the time you spend reading, writing, or thinking about poetry diminishes other areas of your life? Do you have fomo because you're a poet? Poets, particularly serious poets, spend a lot of time on poetry and might even seem overly obsessed. I've had at least one close friend express their pity to me over what I've "sacrificed" for my art. Since May 3rd, I have setting my (internal) alarm for 4 a.m. each morning, getting up, and writing poems. I'm also typing and editing poems and submitting them to journals. My goal is to reach at least one day where I give my full 100% effort to poetry. As of today, I have no regrets about the time I've spent on poetry -- now or ever. In fact, I stopped writing for about 8 years when my kids were young. I wrote a bit here and there but most of it was mediocre because my attention was happily focused elsewhere. And I don't regret the time I spent away from writing poetry and more than I regret the time I'm devoting to it now. The only sacrifice that could have taken place is if I had not started writing seriously again and used being a parent as an excuse to just hobby it on down the road or quit altogether. I'm not built to be a Sunday painter, although I have solid respect for those who are, so... for me passion precludes "sacrifice." Poetry exists outside of the stream of linear time. You can pull out of your focus and go back months later, picking up where you left off or even improving without having tried. What you can't do is ignore that internal voice that lets you know when it's time to give 100% to your art. If you follow that voice, you'll never have to sacrifice anything for poetry to reap creative rewards. Tally Poems Written: 298 Submissions: 48 Rejections: 17 (10 tiered) Acceptances: 0 Poem written today: "Storm Breeze" Categories All My notebook is filling up quite fast since I determined to write a poem every day. Some general observations about writing poems by hand in a notebook: 1) It makes it easier for someone like me who typically overwrites to keep things simple. 2) I usually write the entire first draft without stopping. If I'm typing instead of writing by hand, I tend to revise in process and also look things up! 3) I'm writing fully in my own voice. When I type instead of writing by hand, I notice I tend to echo other poets more frequently. 4) When it comes down to typing up poems, I can take a slow, careful look at the draft and build on it. 5) I tend to keep a sharper focus because I'm writing short poems, usually no more than a single page. 6) The poems, as a whole, are a lot stronger than when I type first drafts. 7) The notebook becomes like an actual book of poetry as I write it and I can read over the drafts, like reading another poet, many times before I get around to typing and revising them. This may only be the case for now. I'm wide open to changing my métier at any time, almost at the drop of a hat. I feel very strongly that a poet should try many different approaches, although I also feel we each have a certain comfort zone. For example, I like to write nature themed poems in tercets. If my life depended on writing a poem, that's probably where I'd start. But that doesn't mean I shouldn't experiment with city themed prose poems -- or sonnets about the "supreme" court. At any rate, I plan to change the size of the notebook when I fill this one up. My biggest problem is finding gel pens that I can rely on and that feel right to me. The last ones I bought are excellent, but they don't have any labels on the actual pens, like absolutely nothing, and I threw the package away so I don't remember what brand they are! Tally Poems Written: 297 Submission Tally: 47 Rejections: 17 (10 tiered) Acceptances: 0 Poems written today: "Park Sprinklers", "Cherry Climb" Categories All As a poet, it's sometimes good to not know how you feel. "Nameless" emotions are often where great poems begin. Famous poems like "Kubla Khan," "The Chariot," or "The Road Not Taken" continue to defy emotional straightjacketing and -- without sacrificing meaning -- continue to lead readers to fresh emotional experiences for which there are no simple quantitative terms, but rather libraries full of analysis.

One of my favorite poets, Hart Crane, wrote a powerful essay on the theory of poetry called "General Aims and Theories." Crane was only in his twenties when he wrote the essay and it was in response to criticisms by Harriet Monroe. Basically, what Crane said was: a great poem can create a new word. Or, more specifically, it is as if a (successful) poem created a new word. A "word" that only that poem can capture, because it represents an emotional state for which we have no literal word. Two things I'd like you to take away from this. The first is that some poems, not all, are best off in creating a new "words", while others are best off celebrating existing "words." The second is that, yes, human beings have that many emotions. More than there are grains of sand in the world, or stars in the sky. We may fixate on the 6-8 basic colors, but we have an entire crayon box (the size of the universe) to color with. If you want to read a great series of poems that deal square-on with he search for a new poetic word, try reading Plath's "Bee Sequence" (click her picture above). What you'll see here is a poet using everything she has to try to understand who she is as an artist. Because Plath was a mystic, it was extremely difficult to find words, or even imagery to convey what she was going through. Like Nina, in Black Swan, she is transforming; she is becoming the Bee Queen. Poetry can lead you to the deepest parts of yourself and the deepest emotions that can be experienced. You have to be careful with intense emotions, but you can't write truly remarkable poetry without going into emotional places past existing "words." Tally Poems Written: 295 Submission Tally: 47 Rejections: 17 (10 tiered) Acceptances: 0 Poem written today: "Plain Poem" |