|

Let me start off by saying that, "The Poem of the World," by Scudder Parker more than lives up to its title. A very tall order, indeed. I was skeptical until I read the first three lines: reveals itself like a doe’s hoof tapping ice till she can drink. I spend a lot of time in nature; this is an authentic and beautiful image. It also works poetically. Once you feel and experience the opening, you quickly realize you're in for a true lyric poem, rooted in nature, that builds tercet after tercet toward revelation. But this poem's not only about theme. Of course, the epiphanic climax is suitably mystical and more than uplifting enough to fulfill titular expectations. But what's remarkable about this poem beyond its archetypal theme is the "melody" of its composition. Even more precisely, the music of its metaphors. For example, Parker compares "the rust of purple on this fall’s / forsythia leaves" to a "small voice / every year, unheard." This bit of synesthesia is but an opening gambit in what is a poem bursting with figurative flights such as a "beach of pebbles that suddenly /starts singing" or "the subtraction / of birds, taking summer with them," -- all stunning and quite exact. Of course, a deeply metaphorical nature poem that builds tercet by tercet toward epiphany also needs beautiful diction, or at the very least, a high degree of melopoeia. Let's taste the penultimate stanza: The poem of the world wants me to wake in my own body; it is astonished I might let these supple bones grow brittle. Say it aloud and realize as you read, that this closing stanza is probably the least sonorous of the nine. That's right, I used the word "sonorous" and I'll continue to do so if it pleases me. I need your opinion on the closing line. Is is satisfying? Go to The Lascaux Review by clicking the pic above and read the poem in full. Then give me your opinion. Categories All

0 Comments

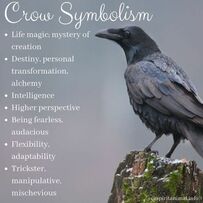

I'm angry about, "Girl, Hotel Mirror," by Laurie Bolger, a poem posted back in September at The London Magazine. Read it in full by clicking the pic above. It's inventive. It's funny. It's sad. And it's a bull's-eye dart right into the heart of our narcissistic, digital age. Add to that, Bolger ushers in a dark, psychedelic tone that lifts to ironic crescendo at the poem's close. So, the poem is musically minded, to say the least. And this is where I start to get angry, because with a piece like this, Bolger's making it a lot tougher on the rest of us who write poems. The poem not only features the crescendo I mentioned, which is constructed almost entirely out of increasingly inventive (and disturbing) surrealistic images; it also features a cast of characters that could (and probably should) round out a provocative one-act play. It has dialogue, dialect, slang, motion, conflict, class struggle, and well, virtually everything but pratfalls. And pratfalls are strongly implied. I count thirty-one total lines. I've seen novelists do much less in 500 pages. Fine, Daniel, but what about the poetry? Well, how's this for an opening? In a hotel mirror, a woman is snogging her own face. The image of a woman kissing her own face is quite funny, but the word "snogging" makes it much more funny. That word does something else, by the way, it sets the speaker of the poem on a superior plane. The quasi-sanctimonious tone persists for most of the poem. When it dissolves, it does so into the previously mentioned crescendo of surrealism, so Bolger washes her speaker right down the drain with everything else. Yet the poem remains. A stunning work of art. There's much more to applaud in terms of pure poetry here, like the enjambment on lines 30-31 that rolls through an onomatopoeic alliteration, then sputters out just as the rational sense of the poem simultaneously dissipates. Have we just watched a maestro smash a violin? Or a rock-star smashing up a guitar? That is exactly what I think we're seeing here. Bolger's smashing up the whole "selfie" culture by not failing at the poem. It's a hit while everything it's about fails. The music survives, not the medium. So, I guess I should be a little less angry, but stay a bit envious and let that inspire me. Categories All When we read a good poem, we fall. You might say we fall deeper into ourselves, deeper into each other, deeper into language, deeper into consciousness. You might even say deeper in love. With poetry. With creativity. With possibility. "Lines Written at Dog’s Head Falls, Johnson, Vermont" by K.A. Hays is one of those poems that will make you tumble. In fact, that's what it's about. Check out the full poem at Agni Online by clicking the picture above. While I usually spotlight one or more technical aspects of a featured poem; in this case, I'm going to focus on theme. Hays plays a bit of game with her theme in this poem. It's a fun game and a thought-provoking one. It starts from the opening line: On a stone by the river what pools in boulders If you wrote the line out like this: "On a stone by the river, what pools in boulders...." it might almost sound like the opening of a thriller or horror story. Instead, this line sets the stage for a confrontation -- or more exactly -- an encounter with nature. The speaker of the poem gazes into the water at pebbles swirled around "a stick bug" -- an image that rapidly gives way to a succession of deeper images of nature-in-motion. The speaker describes "beings" in the water that "hang suspended / head to spine to tail that twists & flicks..." We, along with he speaker, see a microcosm of nature played out in a glance. But there's also epiphany. In the midst of the cycles of life and death, two profound thoughts shine like flares: spinning as the planet heats And the closing line: what were you early what will you become? Clearly, the vision has caused the speaker to sense a connection with nature, with the cycle of life and death, and also to feel the sinister threat of climate change and nature's fall... But is this poem really about nature's fall? Or personal rebirth? Do this. Read the poem straight through. Then read it backwards, straight through left to right, but moving up line by line. It's the cycle of life (and mystery) that never ends. So the true theme of the poem isn't nature's fall; it's our connection to the rhythms of the universe that cycle always, it seems, toward ambiguous but somehow necessary growth. Categories All Recently, I asked you to tell me which of these was better: The crow drank its fill from the snow’s melted puddle, sprayed rainbows flying away. OR The crow drank its fill from a puddle of snow, sprayed rainbows flying. The response was heavily in favor of version 2. A.S. suggested that the poem could be made into a "formal" haiku like this: The crow drank its fill from a clear puddle of snow, sprayed rainbows in flight. I like that. No-one suggested a title, so I'll give it one of my own. Here's the final version: Snow Crow The crow drank its fill from a clear puddle of snow, sprayed rainbows in flight. Can you think of further improvements? Categories All Sylvia Plath is one of the most famous, best-selling, widely anthologized, and universally recognized poets of the twentieth century. Her poems, electric with figurative language and flights of mythic imagination, have thrilled millions of readers and continue to top lists of the most popular and artistically significant poems in American history. Her poetry has earned tens of millions of dollars and continues to sell while most modern poets, even the most celebrated, are read by only a handful of literati.

Plath’s life and work have spawned scores of biographies, plays, critical works, and films. She is widely regarded, along with Anne Sexton and Robert Lowell, as being a founder of the Confessional movement. Her reputation as a feminist, ecologist, novelist, poet, and even mystic is assured in history. How is it possible that this poet, dead by the age of thirty by her own hand, was able to attain such a magnitude of influence and mastery? I’m about to show you... Jo the Crow Casts a Spell Magic night magic Magic moon magic Magic star magic Magic candle magic Magic fire magic Magic rhyme magic Magic rose magic Magic love magic Magic soul magic Magic magic magic So mote it be, magic. Categories All I want to point out two things in today's post. The first is Connemara Wadsworth's excellent poem: "Cows in the Apples" from Lily Poetry Review, which you can read by clicking the pic above. The second is why this poem is so excellent. Of course, as usual, space prevents me from doing more than grazing the highlights. This time, I'm not even going to try to do that. Instead, I want to focus on one aspect of the poem: adjectives. Typically, adjectives ruin a poem. Or threaten to. In this case, like an experienced lion-tamer, Wadsworth makes perennial poem-killers like: "perfumed," "angry," "sweet," and "wet" jump through flaming hoops of originality. How does she do this? First, she hazards an original conceit: breakaway, rebel cows. Second, she drops a surprise adjective: "obedient" in the first line and then proceeds to work against this strong word for the rest of the poem. Wadsworth also bundles each of the potentially banal adjectives with another poetic device. For "perfumed," she uses an alliterative connection to a strong verb "plant." For "angry," she couples the word with the unexpected "bees" which is, of course, a bit of anthropomorphizing. Finally, with "sweet" and "wet," she chooses to slant rhyme them in the closing line -- a line so well executed it should be quoted, along with its accompanying stanza: before they swagger down the road, happy drunks licking bits of sweet apple off wet lips. In general, the rule of murdering your adjectives is a good one. If, however, you can do tricks like this, then you are free to color with even the shortest of crayons. Categories All David M. Pitchford is an exceptional poet. He's written thousands of poems in varied forms on myriad themes, almost always with inventiveness and aplomb. If you click the picture above you'll go to his "Thousand Poem Challenge" blog, no longer current, but full of gems. Scrolling down the abandoned blog, one of the first brilliancies you'll find is: "Kentucky February Snowfall." Let's look at the opening stanza: deep blue rhythm of arctic winter grasps in chill fingers southern haven belies comforts, jails them in frosted winter world when to end? when to end? for warmth they pray though to whom none can certain say, they pray and curse and burn more fuel, wood, gas, coal smoke and steam escaping impotent to heat the world and its arctic sky snowing slow. Note that the entire stanza accelerates like a ball rolling down a steep hill, becoming more and more urgent, even verging on despair with the repeated "when to end? when to end?" and then coming to a perfect close on the word "slow." This is like gunning a Lamborghini to the edge of a death-cliff, then turning it around on a dime, no -- kissing it around -- to a stop, where it shines in moonlight. After this deft volta, Pitchford describes the first inklings of spring -- early signs of winter's death. These are stirrings in the mind and soul, mysteriously timed to and forever joined with the seasons, nature, and the earth. The second stanza is smooth and lyrical, slow and triumphant, leading to affirmation. The repetition of the word "vernal" in the second (final) stanza is perhaps an oversight or, more likely, an echo of the repetition-device in the first stanza, modulated to reflect the inevitability of rebirth and spring. Last notes: Pitchford's logopoeia here is flawless. Particularly in the first stanza. And the poem's closing word is perfectly chosen, don't you agree? Categories All "Roadworks" by Jeff Gallagher is a fine poem posted recently at Amethyst Review. Click the pic above to read it in full. What's impressive about the poem is the way that Gallagher uses language like a light by which to uncover the sacred ritual behind the ordinary world of things. The first stanza reads: The high priests in their hard hats stand round the ruptured gravel, numbed by the spell of an old tree that has wounded the pavement. Gallagher's use of alliteration in the opening line: "high", "hard", "hats" promotes a tone of austere authority. The construction workers are priests. As they repair the road, they become angels doing holy work: As the congregation of cars backs up along this pilgrims’ road, machines fill the cracks, the shrine is rolled flat and anointed with tar. Yet, they seem unaware of their true role. Despite their work, the closing stanza acknowledges that "the cracks will reappear" and that the forces that move nature and human impulse remain shrouded in Divine mystery. It's enough to participate and contemplate. And perhaps offer solace and repairs. Which is what a good poem does. Gallagher's beautifully sustained symbolism, congruent imagery, and careful diction creates a sense of sacred surrealism, a topic and aesthetic idea that I'll return to again in this blog. I consider this a gem of a poem and hope you do, too. Hit talk above or below to let me know what you think of this or any other poem or topic. Categories All |